I saw Saltburn and we need to have an adult conversation about whether Emerald Fennell is good at making movies.

Emerald Fennell already had one strike against her after Promising Young Woman (2020). I am the target demographic for that movie (a white woman in her twenties who had a formative crush on Bo Burnham). But Promising Young Woman is a Bad Movie.I spent ages trying to figure out what exactly it was trying to say, before realizing that it actually has nothing to say at all. It’s the worst kind of movie: aesthetically political while having no actual politics. There’s no there there.

Morale was low going into Saltburn. But I got my butt in a seat because I wanted to drink a Diet Coke, eat my little popcorn, and pay my respects to Jacob Elordi’s saucy little eyebrow piercing.

My verdict on Saltburn: It’s not cinema.

Saltburn is only a movie in the sense that it lasts approximately two hours and I had to pay $12 to watch it. But I go to the movies to laugh, to cry, to care. Saltburn made me do absolutely none of those things. Saltburn is The Talented Mr. Ripley (1999) if The Talented Mr. Ripley was less fun and less gay and also bad. Literally the best part of my Saltburn viewing experience was the trailer for the Zendaya threesome tennis movie.1

But I’m experimenting with being less of a hater, so I’m going to start off with the two things I liked about Saltburn. First, I liked Carey Mulligan’s heart tattoo that says “Daddy.” I’m considering getting one. Second, Jacob Elordi was hot.

Alright, with that out of the way, I desperately need to talk about why this movie sucks.

First, Saltburn, despite my expectations, was not a queer, horny, “eat the rich” romp. Instead, Saltburn was a weirdly conservative movie about the destructiveness of unreciprocated homosexual desire.

Saltburn follows Oliver (played by Barry Keoghan, in fine “Weird Little Guy” form), a semi-closeted queer Oxford student. As the movie progresses, Oliver’s revealed to be a pathological liar and eventually kills the straight man who fails to reciprocate his affections. In short, pathological closeted queer man kills the object of his unrequited affections. This feels like Fennell looked at every bad stereotype about queer men in media and said “mmm, I’ll take the lot.”

To be clear, I’m in no way opposed to gay villains. Mark Harris has a great article in the New York Times, “Yes, These Gays Are Trying to Murder You,” in which he talks about the depiction of gay villains onscreen and offers a number of examples of interesting reinterpretations of the trope. Season 2 of The White Lotus, The Talented Mr. Ripley, and Fellow Travelers (which falls more into a Don Draper anti-hero category) all come to mind as playful or thoughtful re-imaginings.

But Saltburn is neither playful nor thoughtful. Instead, the film reads as a straightforward, by-the-numbers depiction of the “Depraved Homosexual” trope.

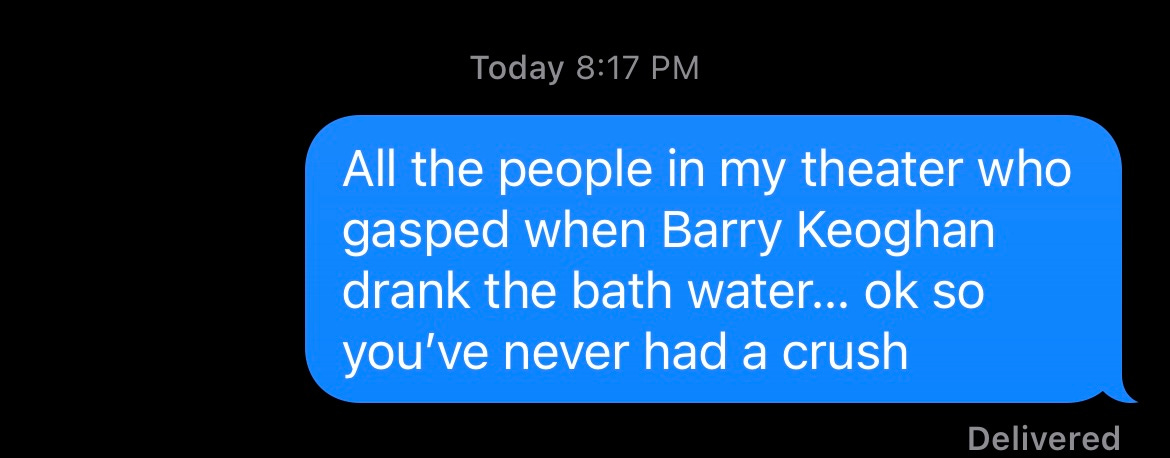

In Saltburn, queer pleasure is always confined to the shadows (literally, in one scene), and is only ever a source of shame, disgust, and, eventually, tragedy. Take the scene in which Oliver (the semi-closeted queer hero) drinks Felix’s bathwater after secretly watching Felix masturbate in the bath. This scene depicts queer desire as one-sided, voyeuristic, and, based on the audience reaction in my theater, disgusting.

Or take the scene in which Oliver appears in Farleigh’s—his male rival for Felix’s attentions—bedroom after Farleigh attempts to humiliate Oliver via karaoke (I would love to dive deeper into how one of the most threatening moments in this movies is … karaoke? But word limits). The scene opens with Oliver perched on top of Farleigh in Farleigh’s bed. The pair are backlit by the window, and Oliver resembles the incubus in Henry Fuseli’s The Nightmare (or Doja Cat in the “Demons” music video). Oliver gives Farleigh a handjob while threatening him. This is the only queer sex scene with two people, and it’s focused fully on rivalry and power rather than reciprocal pleasure.

Later in the film, Felix learns that Oliver lied about being poor to get Felix’s attention, and Felix (understandably) pushes Oliver away. With the object of his love firmly out of reach, Oliver poisons Felix, and later has sex with Felix’s freshly-dug grave while sobbing. This scene is a grotesque depiction of the destructiveness of unreciprocated queer desire. I hated it! There is not a single scene of mutual queer pleasure. In the world of Saltburn, queerness is tragedy.

Maybe Fennell wanted to say something about how heteronormativity represses queer people and desires. But like … yeah, we know. That narrative has been done before (and better) almost twenty-five years ago in The Talented Mr. Ripley. Fennell has nothing new or interesting to say about the subject.

I think that’s because Fennell actually isn’t interested in queerness beyond it being perceived as transgressive. Fennell isn’t interested in making a “queer” movie, she’s interested in making a movie about “obsessive love.” But she forgot that in making a movie about obsessive love between two men, she needed to consider the politics and tropes associated with that choice. Queerness shouldn’t just be deployed as an aesthetic to make a movie seem “edgy.” It’s giving t.A.T.u. (the girls that get it get it).

Second, Fennell’s addiction to including “big twists” in her films sabotages any potential class commentary Saltburn could offer. Halfway through the movie, it’s revealed to both Felix and the audience that Oliver lied about being poor to get Felix’s attention. Oliver is, in fact, from a nice, middle class family. Felix is repulsed by Oliver’s lie, which prompts Oliver to kill Felix at Oliver’s birthday bacchanal.

Fennell fucks up the entire movie with this twist. By withholding Oliver’s lie from the viewer until this moment, the viewer, like Felix, feels tricked by Oliver. The viewer, who believes they’ve been following Oliver’s perspective for the entire film, is abruptly alienated from him. There’s no heart to the movie, no one the viewer is rooting for. After this twist, I found myself empathizing with Felix, the aristocrat, which is an incoherent development for a movie that masquerades as an “eat the rich” satire.

Oliver proceeds to kill off Felix’s entire family, and ends up inheriting Saltburn. A flashback sequence near the end of the film reveals that this was Oliver’s plan since the moment he started at Oxford. I’m sorry, huh? This twist makes no sense. Was Oliver always planning to kill off Felix? If so, why was Oliver so broken up about his death? We’re meant to believe Oliver showed up at Oxford cosplaying as a poor student to inherit an estate he didn’t know existed? Emerald, I’m tired.

After the “big reveal,” the whole second act of the movie didn’t work for me. I didn’t care about Oliver or the residents of Saltburn, so I didn’t care who lived or died. Oliver can kill whoever he wants, it’s none of my business. I’m not going to root for this middle class pathological liar to inherit an estate when he could be sitting in his parents’ nice semi-detached and eating mince pies.

Contrast this choice to withhold key information about the main character with The Talented Mr. Ripley. The Talented Mr. Ripley is filmed entirely from Tom Ripley’s perspective. The viewer knows everything about Tom Ripley, and follows his crimes in real time. The tension isn’t generated from artificially withholding information from the viewer, but rather from wondering whether Ripley will get away with is crimes. Because you always occupy Ripley’s perspective, it’s immensely satisfying to watch Ripley get away with his crimes. In contrast, there’s no organic narrative tension in Saltburn. The tension is entirely manufactured by the filmmaker, leaving the viewer unable to really invest in Oliver’s killing spree. With no emotional investment in Oliver, the second half of the movie feels like a soulless exercise in hitting plot beats.

I cannot get over how bad this movie is on every level except, if I’m feeling generous, a technical one. There’s a decent tracking shot at the end that follows Barry Keoghan dancing naked through Saltburn while “Murder on the Dancefloor” plays. I would maybe like this movie if it was just that scene. I want Saltburn (Director’s Cut) (2 Minute Version).

Things I Learned While Writing This Newsletter

Jacob Elordi was interviewed by Jimmy Kimmel in the lead-up to the release of Priscilla. Jimmy Kimmel asks Jacob Elordi how tall he is, and Jacob Elordi says “6’5.” the audience immediately starts cheering. Jacob Elordi literally says nothing other than his height, and the audience is hooting and hollering. This is so cursed.

Emerald Fennell’s dad has a blue link on Wikipedia. Should nepo babies be fined when they pretend that their movie will be an “eat the rich” satire?

I will literally never forgive the studios for delaying this movie due to the WGA strike.